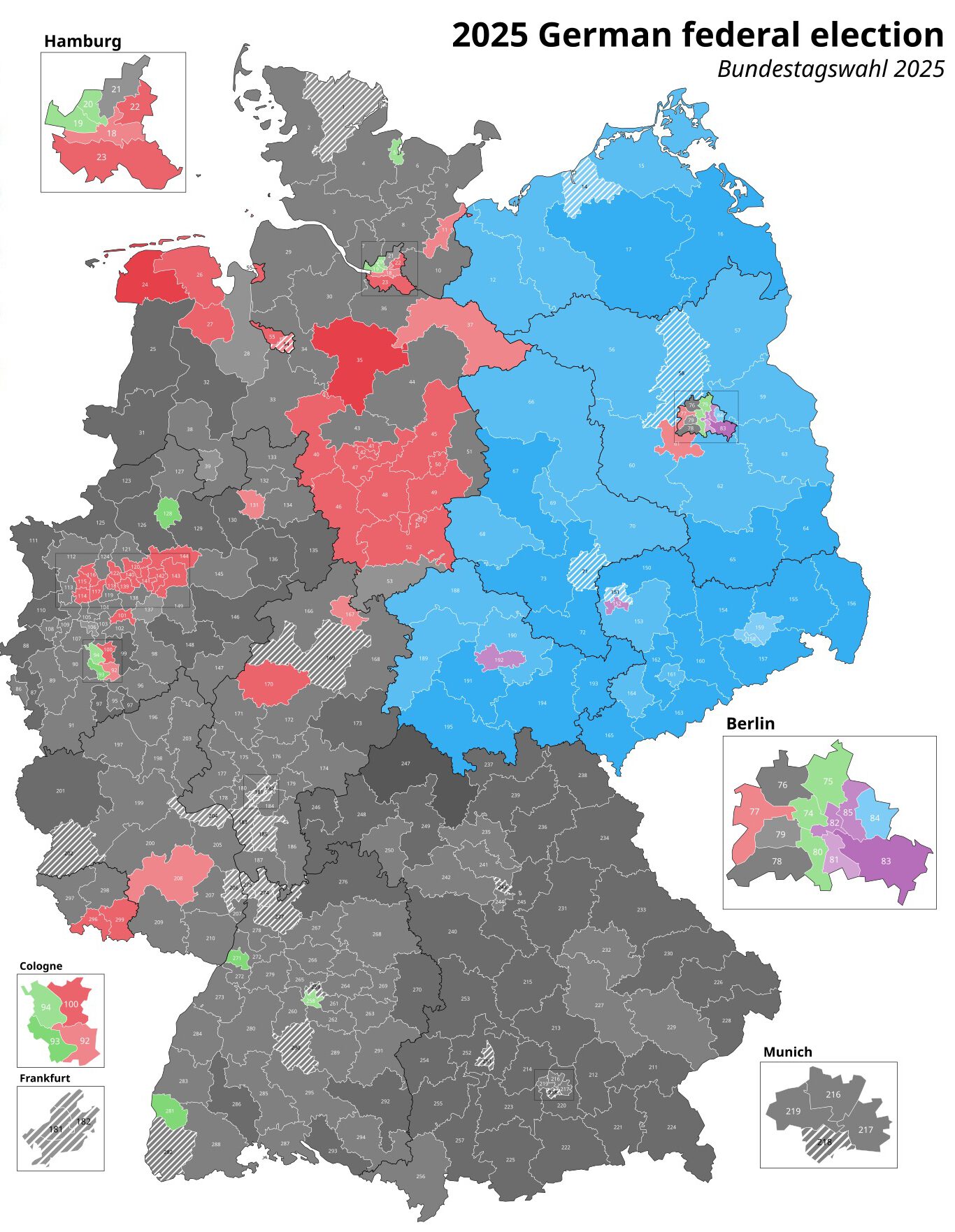

When the results of the last German election came out on the evening of February 23rd, a friend of mine living abroad texted me “Apparently, the Wall is still standing.” He was of course referring to the quite striking difference in voting results between states formerly belonging to East Germany, where the far-right AfD is now the strongest party, and states formerly belonging to West Germany, where the conservative party CDU/CSU took the lead. In the following days I saw numerous headlines, both in national news outlets and abroad, using what’s been called elsewhere a “polarization narrative.” The results were framed as reflecting a “polarizing election,” or the fact that Germany is (now) “polarized”.

The election results are worrying for a number of reasons. What I want to convey here, however, is that a healthy P&E perspective shows us that a two-colored election map isn’t quite enough to conclude that the German electorate is now polarized, polarizing, or more polarized than before. What is more, pushing the polarization narrative has the perhaps unintended, but nonetheless negative side effect of obfuscating a lot of the values and opinions that we do share with one another.

1. Four senses of “polarization”

“Polarization,” both understood as a state or as a process, has been used to refer to at least four very different things. One can speak of opinion polarization, network polarization, affective polarization, and group polarization. In other words, “polarization” is not a monolithic concept. When someone claims that a group is polarized, it is thus very important to first clarify what they mean by “polarization.”

As its name suggests, opinion polarization is about the distribution of the views – i.e. opinions, values, or even preferences – on a particular scale or dimension. If you search online for images illustrating polarization, you’ll find plenty of blue-and-red graphs showing, on the one hand, increasing “distances” between the opinions of Democrats and Conservative US voters on various issues and, on the other hand, that the voters in those groups tend to be more and more like-minded. To use a more contemporary example from Germany, it could be that if we look at the opinions of the residents of former West and East Germany, say about immigration policies, we will find that these opinions are becoming increasingly distant between these two groups, while increasingly similar within these groups. These two aspects reflect how most studies on opinion polarization understand the concept, namely as a function of intra-group homogeneity, and inter-group heterogeneity. There are various ways to measure this, from standard statistical tools like variance or differences in means, to specific indices developed to strike a particular balance between intra-group homogeneity and inter-group heterogeneity. Some also take into account other factors, for instance how many sub-groups there are in the population, how much the opinions cluster around particular sets of views, or around particular identities.

On the other hand, network polarization, also sometimes called network segregation, refers to the clustering of similar individuals within social networks. Unlike opinion polarization, network polarization is not primarily about how opinions are distributed in the population. Rather, it is referring to the patterns of “connections” within a specific social network. To take an example from US politics again, if you search for “network polarization”, you’ll find plenty of graphs that illustrate the notion relatively well. They show large networks with two main clusters or communities, a “blue” and a “red” one, with lots of connections between the members of each community, and comparatively much fewer between the communities. Again, to take an example from Germany, it could be that the social network of far-right voters is very dense, i.e. they have a lot of connections with one another, that the same holds for rather left-wing or liberal voters, but that there are barely any connections between those groups. These communities form some kinds of “bubbles” or “echo chambers”, so to speak, where the members are much more often exposed to people who look and think like them, than to those of people who look and think differently. This applies of course to our modern, online social networks, but also to offline social connections like friendships, neighbors, or colleagues. Just like for opinion polarization, there are a number of ways to measure network polarization, ranging from standard notions from network theory, like centrality or diameter of communities, to more specific indexes developed precisely for that purpose.

Our third notion is that of affective polarization. Affective polarization reflects the extent to which group members have (increasingly) negative feelings toward members of other groups, and vice versa for members of their own groups. So affective polarization is less about opinions or network connections than about the emotions or feelings that one has towards in-group vs out-group members. In affectively polarized environments, the “others” come to be seen not just as people with different ideas but as threats or enemies. In the German context, for instance, this could mean, on the one hand, that resident of the former West and East would increasingly look at each other with suspicion, ones considering the others, say, “arrogant” or even “hypocrites”, while the other consider the one, for instance, “backward.” Interaction between these groups, on the other hand, would then become increasingly combative and hostile, both offline and online. When we hear that social media or online communication foster polarization, this is often meant in this affective sense. Affective polarization has been typically measured using “feeling thermometers” in surveys, or by automated classification and analysis of online posts, for instance in X/Twitter.

The fourth and final notion of polarization, sometimes called “group polarization”, is rather a psychological phenomena in which opinions radicalize during group discussions. One might think that group deliberation is good because it helps us get to better-informed, and perhaps more nuanced opinions. There is quite a large body of research in social psychology and political science showing that this is often the other way around. While discussing with others, especially with like-minded ones, we often get more confident of our own views, and even form stronger or more radical ones. This is what has been called “group polarization.” Note that this is quite different from the three other notions. For one thing, group polarization can occur even in a “single” group. It doesn’t require the existence of two “poles,” “communities,” or “others.” Also, it is specific to individuals in group discussions, while the other notions are more aggregated or “macro” observations, about the distribution of opinions, the network connections, and or the ingroup/outgroup feelings.

2. Why do we care about polarization? And is Germany polarized?

Why do we care about polarization then? Or, in other words, why is the “polarization narrative” often phrased as sometimes alarming or to worry about? One thing that is clear from the empirical and theoretical literature is that, even though the four senses of polarization are conceptually distinct, they are often correlated and feed into each other. A heavily segregated social network might, for instance, foster on the one hand in-group radicalization of opinions (i.e. group polarization), but also on the other hand an increasing alienation from outside perspectives, which in turn can lead to stronger affective polarization. Affective polarization is in fact often identified as a likely consequence of all three other forms of polarization, and many social scientists have pointed out the inherent tensions that can arise in an affectively polarized context. Seeing the others as enemies or thread of course hinders mutual understanding, can lead to supporting more intolerant and reactionary policies, and create political deadlocks.

With this in mind, let us go back to the election results, and ask ourselves whether they show us that “Germany is polarized.”

Starting with the more obvious candidate, opinion polarization, the thought would be that the results of the last election show us that the opinions or even values of the people living in former East and West Germany are moving apart, i.e. getting more “distant” from each other. But is that really the case? What emerges from the literature in political science and economics is that a split election – be it across age, income, education level or, like in the recent German election, geographical regions – does not entail that the underlying opinions of the voters are polarized. The reason for this is, quite simply, that people vote for all sorts of reasons. So even very divided voting results are not necessarily a sign that the underlying opinions of the voters are divided accordingly. At most, a divided result like those we just had might reflect what has been called “elite” or “political” polarization, i.e. polarization in the rhetoric of the political elites, or between the parties themselves. But that is still something quite different from opinion polarization.

The same hold for network, affective, or group polarization. There is no necessary correlation between split election results and a polarized or segregated social network. In fact, some studies from the 1990s have documented cases where increase in opinion or political polarization seem to have gone together with decreases in network segregation, possibly through group polarization. As bad as bubbles can be, they can also shield from opinions or people that would otherwise lead you to radicalize. Along the same lines, split elections can of course come together with affectively polarized discussions, but they need not to.This, of course, doesn’t mean that Germany isn’t actually polarized, in either senses of the terms. It is probably polarized in some sense, or on some key questions like migration or defense policies. My goal here is only to issue a word of caution. The split election result might be a symptom of deeper cleavages in Germany, but the former is neither necessary nor sufficient for the latter. We can have split elections in a non-polarized environment, or fairly unified results hiding a very polarized electorate. In fact, pushing the polarization narrative might not only be incorrect but also detrimental. It makes us focus on the couple of salient, controversial issues on which there is perhaps some degree of polarization, and leaves aside what is arguably the much larger common ground and set of values that we share, and that are becoming increasingly important moving forward.

Leave a Reply