Social groups come in many different shapes and sizes, from sports teams to academic clubs to political organizations. Some of them have a very loose structure, if any, such as crowds or temporarily formed communities at music festivals. But many are organized in some way or another through the relations between their members. Usually, these groups maintain their identity even as their members come and go. However, for those familiar with the tale of the ship of Theseus, it is a bit of a puzzle how it can be so. Moreover, a social group is not uniquely identified by its members alone. Different groups may share the same members over time. Let’s then explore what all social groups with an internal structure have in common and see what it takes for a group to persist over time despite changes within it.

What is a social group?

Assume that social groups really exist, that is, that they are not merely a conceptual or a linguistic tool that helps us to describe the collection of individuals and the interactions between them, but rather a real object that exists out there in the external world like chairs, apples, and atoms. Just as cells in a human body come and go, while an individual maintains her identity, so too does a social group as new members join and old ones leave. No specific set of individuals is necessary for the persistence of the group. For example, FC Barcelona may “never be the same” without Messi, but nonetheless, it is still the same team. The puzzle of how this is possible has already been explored in the ancient tale of the ship of Theseus. The story raises the question of whether an object remains the same when all its components are replaced over time, using the metaphor of a ship whose parts are gradually exchanged until none of the original components remain. Is it still the same ship?

I am looking for a formal definition of a social group that fulfils the following criteria:

- It explains how a social group with an internal structure can maintain its identity over time with the change of membership.

- It explains how groups with the same members over time, but which are organized differently can have different identities.

The most promising option capable of tackling both issues is regarding groups as variable embodiments.

Groups as Variable Embodiments

Hylomorphism is an idea proposed by Aristotle, which states that physical entities consist of both matter and form. Matter is what we typically think of as ordinary physical parts, while form gives the object its structure and shape. For example, a sandcastle’s form is the shape of the castle, and its matter is sand.

Kit Fine developed this idea into the theory of embodiment, which allows us to understand groups as having members (matter) and form (the way the members are organized). According to Fine, there are two forms of embodiment: rigid and variable.

One way to think about an object is that it consists of parts. When we sum those parts together, we construct an object. In this naive view, there is no need for a blueprint/ instruction on how to assemble the parts of an object. However, we might notice that, let’s say, the same two buckets of sand can be used to make different objects: a sandcastle or a sand animal. If we want to uniquely represent an object as the sum of its parts, we need additional information on how to do this. This is where the concept of rigid embodiment comes in.

According to Fine, the solution is to still consider an object as a composite of parts but to, in addition, state the relation R between them at a specific moment in time. This is what Fine calls rigid embodiment. It can be used, for example, to describe the current state of a social group consisting of Magda, Tom, and Robert, and to specify the relations between them (Magda is the boss of Tom and Robert, etc.). This is important because, just as buckets of sand can be used to create different objects, Magda, Tom, and Robert can be “building blocks” of many different social groups at any given time. Rigid embodiments therefore specify not only which members are part of the group, but also the relationship between them in that group at any given time. However, groups change their members over time. Rigid embodiment cannot account for that since it describes what a group looks like at a particular time. Therefore, we need another concept: variable embodiment.

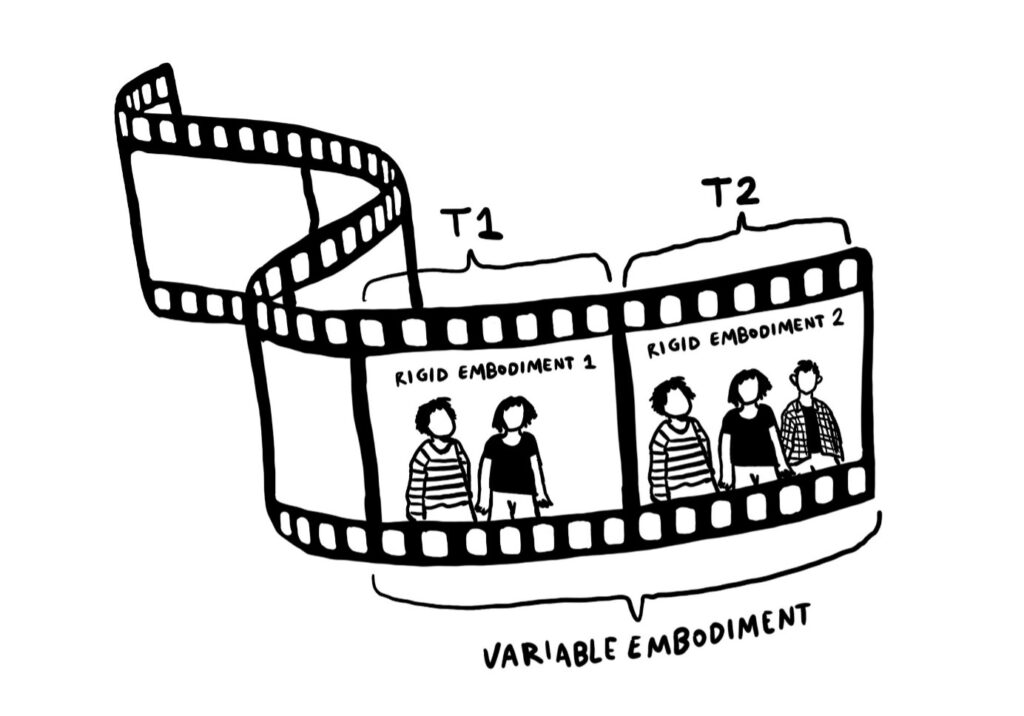

If you are old enough (or passionate about photography) you may remember that old cameras used a roll of film to store the pictures before they were developed. If we think of rigid embodiments as frames on a roll of film, variable embodiments are a whole roll, with the length of the roll indicating the passage of time (see Picture 1).

Picture 1 @glenningdahl

Variable embodiment consists of a collection of rigid embodiments assigned to each moment in time. To create a variable embodiment, we need to have an instruction on how to choose which rigid embodiments should be a part of a variable embodiment at time t. We can call this instruction function F(t) (the principle of variable embodiment). In the metaphor of a roll of film, F(t) will tell us which photographs were taken on the same roll of the film, and in what order in time.

Following Fine, I suggest that social groups are variable embodiments that manifest themselves at each instance as rigid embodiments. At any given moment, the rigid embodiment consists not only of the current members of the group but also of the relationship between them. This collection of rigid embodiments over time constitutes variable embodiment.

Treating a group as a variable embodiment deals well with a change in group membership over time. At each instant F(t) picks out only those individuals who are currently members of the group and the relations between them given by R. If the membership changes over time, F(t) will pick out different people who now form a new rigid embodiment. F(t) is then something that unites different instances of group members and the relation between them over time.

Look again at the picture 1. In the first frame, we have Magda and Tom. Let’s say the picture was taken in November. In the second frame, Robert has joined the group. Let’s say that that picture was taken in January. Then we have two rigid embodiments:

Rigid embodiment 1: (Magda, Tom) and R1 between them

Rigid embodiment 2: (Magda, Tom, Robert) and R2 between them

A function F(t):

F(November) = Rigid embodiment 1

F(January) = Rigid embodiment 2

And those two frames together form a variable embodiment.

Groups, Narratives, and a Principle of Variable Embodiment

Let us leave the ontology for a moment and return to a more casual way of talking about social groups. Recall that we are looking for something that binds the various members of the group together, and what makes a particular social group that group and no other. One candidate for that “something” is a group narrative.

The most relevant definition of narrative for our purposes comes from the Merriam-Webster Dictionary which states that narrative is “a way of presenting or understanding a situation or series of events that reflects and promotes a particular point of view or set of values”.

What is the role of narrative in the formation of an identity of the self? Narratives are stories we tell ourselves to understand past, present, and future events, and to attribute an action, experience, or psychological trait to a person. There is a parallel between a narrative view of personal identity and what we might call a we-narrative, which is useful to account for a group narrative. We are generated and sustained through actions and practices, especially joint actions and narrative practices, for example, group members working together on a task or sharing struggles about their working day in the organizations they are part of. In this way, groups can plan out long-term projects and form what Shaun Gallagher and Deborah Tollefsen call distal intentions (D-intentions).

D-intentions are those intentions that are not concerned with immediate actions, but with a great future goal. For an individual, D-intentions provide a sense of being in control of one’s actions. In groups, they help coordinate actions among the members. A group itself “may collectively attribute agency to itself via both prospective and retrospective narratives processes, where narratives are formed in a way that goes beyond any one individual”. This means that group members can collectively look at what they have done as a group in the past and what they intend to do as a group in the future, and in this way create a narrative that binds them together.

How does this talk of narratives connect with what I have said earlier about groups being variable embodiments? Recall, that the function F(t) (the principle of variable embodiment) is responsible for picking out the group members and relations between them for each moment in time. I propose that the narrative of the group is what determines the shape of this function. The narrative is what tells the function how to behave and which rigid embodiments should be a building block of which variable embodiment.

In this way, what exists in the real world are those social groups that have at least a minimal form of structure and narratives that bind their collection of members together over time. It is a group narrative that determines the internal structure of that group over time. This allows for a narrative to “take on a life or a power of their own, can transcend individuals and come to support an instituted structure”.

There is a way to understand how it is possible that a social group maintains its identity without it being determined solely by group membership over time. We have seen that relations between members are also important when defining a social group. Moreover, I have suggested that group narratives determine which people are members of a social group at each point in time, and the relations between them.

Leave a Reply